In part 1, I set out the key aims of the finance system, the

central pillars of the Anglo-Saxon model which is the predominant school of

thought on how this system should be governed and a brief discussion on whether

this system was effective. In this post, I will explore whether, even if the

system became more effective, it is fair

(and in particular whether it is regressive) and whether as a career it can be

conducive to the good life.

Let me start by saying that is very rare to meet someone in

the city who is not clever, diligent and energetic (in some cases almost as good as teachers, doctors and engineers!) . That is not a criticism

that can be fairly attributed to city workers. The real problem is that various

mechanisms mean that they cream too much out of the saving-investment-return

system I described above. Geoff Mulgan raises this in his book The Locust and the Bee: Predators and Creators in Capitalism’s Future.

In the book Mulgan argues that there are two categories of cog in the

capitalist system, namely the bee, who creates value, and the locust who tries

to cream off value from things that already exist (rent-seekers) or off the back

of the bee. The problem with finance is that there are too many locusts.

Between you depositing your money into a savings scheme, and the money being

invested and earning a return and then being returned to you, the fees earned

by the finance system are staggering. In a typical cycle your savings will be

charged a fee by an asset manager, a fund manager, a broker and the company’s

management before being invested into something useful (and that’s an example

of a short route). On the way back a proportion of any returns will be paid to

the company’s management, to the fund manager, to the asset manager and only

then returned to you. Examples,

which from my experience would not be uncommon, include:

Let me start by saying that is very rare to meet someone in

the city who is not clever, diligent and energetic (in some cases almost as good as teachers, doctors and engineers!) . That is not a criticism

that can be fairly attributed to city workers. The real problem is that various

mechanisms mean that they cream too much out of the saving-investment-return

system I described above. Geoff Mulgan raises this in his book The Locust and the Bee: Predators and Creators in Capitalism’s Future.

In the book Mulgan argues that there are two categories of cog in the

capitalist system, namely the bee, who creates value, and the locust who tries

to cream off value from things that already exist (rent-seekers) or off the back

of the bee. The problem with finance is that there are too many locusts.

Between you depositing your money into a savings scheme, and the money being

invested and earning a return and then being returned to you, the fees earned

by the finance system are staggering. In a typical cycle your savings will be

charged a fee by an asset manager, a fund manager, a broker and the company’s

management before being invested into something useful (and that’s an example

of a short route). On the way back a proportion of any returns will be paid to

the company’s management, to the fund manager, to the asset manager and only

then returned to you. Examples,

which from my experience would not be uncommon, include:

One of the city’s most insidious impacts on society has been its ability to attract the brightest and best from Britain’s education establishments. I must admit at the age of 16 I weighed up whether to study engineering or economics / finance. A mixture of monetary incentive and prestige drew my young self to think of finance as the more worthwhile and rewarding. I do not know whether this dilemma has impacted other young, ambitious people – my concern is that it is quite a few. The cleverest (across the subject board) two people I knew at school / university ended up being a trader and a corporate tax lawyer respectively. In a recent visit to Cambridge I bumped into a young man, with a string of 1st behind him who had just been to the Pitt club (Cambridge’s answer to the infamous Bullingdon Club). In a brief conversation he claimed he would soon be ‘a rainmaker in the city’ and ‘rolling in it’. Apart from the fact that over the next few years of his life he will finding himself filing legal documents at 3am on more than one occasion, and also that this was a decidedly toffish and arrogant thing to say, it is also a great shame that this bright individual saw this city lifestyle as the pinnacle of aspiration. By all means be a lawyer, but don't close off many types of law outside of corporate / finance law.

If indeed the city does deprive other parts of society and other industries bright, ambitious individuals, then beyond being a massive obstacle to having a healthy, balanced economy it can only lead to a more elitist, London-centric and culturally separated society.

Some of the worst examples of greed I have seen in the city have been where the private sector takes advantage of the public sector – essentially taking social money (i.e. mine and yours) and transferring into rich, private hands. There are many examples a friend* of mine has witnessed, the following being stark examples

Too many locusts, not enough bees

Let me start by saying that is very rare to meet someone in

the city who is not clever, diligent and energetic (in some cases almost as good as teachers, doctors and engineers!) . That is not a criticism

that can be fairly attributed to city workers. The real problem is that various

mechanisms mean that they cream too much out of the saving-investment-return

system I described above. Geoff Mulgan raises this in his book The Locust and the Bee: Predators and Creators in Capitalism’s Future.

In the book Mulgan argues that there are two categories of cog in the

capitalist system, namely the bee, who creates value, and the locust who tries

to cream off value from things that already exist (rent-seekers) or off the back

of the bee. The problem with finance is that there are too many locusts.

Between you depositing your money into a savings scheme, and the money being

invested and earning a return and then being returned to you, the fees earned

by the finance system are staggering. In a typical cycle your savings will be

charged a fee by an asset manager, a fund manager, a broker and the company’s

management before being invested into something useful (and that’s an example

of a short route). On the way back a proportion of any returns will be paid to

the company’s management, to the fund manager, to the asset manager and only

then returned to you. Examples,

which from my experience would not be uncommon, include:

Let me start by saying that is very rare to meet someone in

the city who is not clever, diligent and energetic (in some cases almost as good as teachers, doctors and engineers!) . That is not a criticism

that can be fairly attributed to city workers. The real problem is that various

mechanisms mean that they cream too much out of the saving-investment-return

system I described above. Geoff Mulgan raises this in his book The Locust and the Bee: Predators and Creators in Capitalism’s Future.

In the book Mulgan argues that there are two categories of cog in the

capitalist system, namely the bee, who creates value, and the locust who tries

to cream off value from things that already exist (rent-seekers) or off the back

of the bee. The problem with finance is that there are too many locusts.

Between you depositing your money into a savings scheme, and the money being

invested and earning a return and then being returned to you, the fees earned

by the finance system are staggering. In a typical cycle your savings will be

charged a fee by an asset manager, a fund manager, a broker and the company’s

management before being invested into something useful (and that’s an example

of a short route). On the way back a proportion of any returns will be paid to

the company’s management, to the fund manager, to the asset manager and only

then returned to you. Examples,

which from my experience would not be uncommon, include: - Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) - an investment bank will often advise a company on how much it should pay to buy another company. In the chain I describe above, this is essentially another link in the chain where a company invests in another company rather than investing directly in something useful. Typically, advisors (including an investment bank) may earn 3-4% of the total price paid for the company. Whilst the work required from the investment bank may be arduous and detailed, there is no reason why M&A advisers should be earning these fees. Indeed the benefits for the individuals involved could be ridiculous. If you’re working on a deal for a company worth £1bn (not unusual) £30-40m could be paid out in fees. Say one bank is responsible for the majority of these fees (50%, the rest going to consultants, lawyers and accountants) and employs 10-15 people during the deal. In the worst case this would be £15m shared amongst 15 people. Assuming the bank gets its cut (50%), this would be c. £500k per employee over a 4-12 month time period. The senior managers would get a greater share – essentially setting themselves up as millionaires for simply doing their job (and remember they are not creating value, simply taking a cut of a stream of money)

- Private Equity - Without going into the same level of detail, I know of fee structures for private equity funds where similar groups of people will make similar returns on an annual basis for essentially sitting on a stream of money passing back to the original savers.

- CEOs - Another cog in this system who is more locust than bee are the executive management teams of big business (say worth >£500m). Again these are people who will be paid a six-figure salary and bonus of upto 100% of their current salary and a long term incentive plan often running into the millions if they hit various long term targets. Again I would say that these people are rare in terms of their leadership skills, understanding of a sector and experience. However, they are not the source of value for businesses. In the area I have worked in I’m not really sure how they could be. The infrastructure sector is about big bits of kit (water pipes, electricity networks, trains, oil storage facilities, schools and hospitals) which basically earn a return because they are there and are maintained to a reasonable standard. The CEOs of big water companies and energy companies simply cream off value that they do not themselves create – there is not other way I can put this. When I asked the firm I worked for, who own some of these companies and who sit on some of the remuneration committees that set levels of pay for management, why such high levels of pay were tolerated I more or less got a shrug of the shoulders. The reason they gave was that my company had its hands tied in terms of what it could do - we were simply at the mercy of the "market".

Brain Drain

One of the city’s most insidious impacts on society has been its ability to attract the brightest and best from Britain’s education establishments. I must admit at the age of 16 I weighed up whether to study engineering or economics / finance. A mixture of monetary incentive and prestige drew my young self to think of finance as the more worthwhile and rewarding. I do not know whether this dilemma has impacted other young, ambitious people – my concern is that it is quite a few. The cleverest (across the subject board) two people I knew at school / university ended up being a trader and a corporate tax lawyer respectively. In a recent visit to Cambridge I bumped into a young man, with a string of 1st behind him who had just been to the Pitt club (Cambridge’s answer to the infamous Bullingdon Club). In a brief conversation he claimed he would soon be ‘a rainmaker in the city’ and ‘rolling in it’. Apart from the fact that over the next few years of his life he will finding himself filing legal documents at 3am on more than one occasion, and also that this was a decidedly toffish and arrogant thing to say, it is also a great shame that this bright individual saw this city lifestyle as the pinnacle of aspiration. By all means be a lawyer, but don't close off many types of law outside of corporate / finance law.

If indeed the city does deprive other parts of society and other industries bright, ambitious individuals, then beyond being a massive obstacle to having a healthy, balanced economy it can only lead to a more elitist, London-centric and culturally separated society.

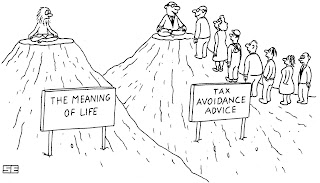

Tax, Regulation and

PPP

Some of the worst examples of greed I have seen in the city have been where the private sector takes advantage of the public sector – essentially taking social money (i.e. mine and yours) and transferring into rich, private hands. There are many examples a friend* of mine has witnessed, the following being stark examples

- The worst example of greed she saw was whilst working at an investment bank. The team she was working for had recently closed a deal whereby they had agreed to finance the building of a public hospital under a PPP contract. Essentially, the private sector (a builder and financier) agree to build a hospital and the government / nhs agree to pay a guaranteed rent once it is completed. The team at the time was congratulating itself for earning upfront fees and profit (legally) in the region of £20-30m (amongst let’s say 5-7 people) whilst the hospital is now struggling to stay open due to rental obligations. Now whilst part of the issue was bad procurement by the government, there is a sense of injustice here that I think is difficult to argue against.

- In another PPP project a company she worked for sold a set of schools for £19m that it had paid c. £7-8m to develop and build. What’s worse is that a few key individuals would have shared a bonus from this of between £500k to £1m (estimate). The government will still be paying a rent for these schools for another 20 years.

- This friend has now worked on three deals (of project worth £1-2bn) where fees made by lawyers, consultants, banks and accountants will have run to c. £30-50m per deal for c. 6 -18 months work. Again this will have been shared amongst a small pool of individuals with the potential to make 3-5 key people £250k+ in bonuses per deal and ensure that several individuals could survive on very healthy £50-100k pa salaries. Again the value creation in each of these cases will be spurious. All three deals will have involved the state or state-like bodies directly being worse off due to these fees.

- In his time in the city, she spent a good amount of time working on developing structures with the direct aim of reducing tax costs or avoiding new tax laws used to clamp down on previous loopholes that were targeted. What struck her was the sheer amount of time, effort and complexity that people were willing to engage with in order to achieve these outcomes. She was also astounded by how an investor would see a £ earnt from creating value (e.g. through investing in a new project) as worthy as a £ from an elaborate new tax structure. She, for instance, was staggered when she witnessed a scheme whereby a company was looking to make a further £3m profit by re-structuring its tax affairs on a c.£45m investment.

Is this the good

life?

Within the city there are a variety of different types of job

associated with making the saving-investment-return cycle work. At the top end

of this spectrum in terms of pay will be corporate and finance lawyers, traders

(sales, trading and research), m&a bankers, asset managers, fund managers,

consultants, accountants, insurance brokers, actuaries and tax professionals. I

cannot talk for many of these professions, but in relation to the two

organisations I did work for (a bank's M&A team and private equity fund) I would

say the following

- The career path for a graduate is great in terms of early responsibility

- The people you work with will be very smart, diligent and energetic (sometimes overly so). There will be a spattering of the arrogant and mean, but at the same time there will be some genuinely warm characters who simply want to do good for themselves and their dependants and take no pleasure from putting down others.

- There are several factors which would detract from living a happy life, namely

- Anxiety due to the hire and fire nature of the world

- The areas I worked in demanded very long hours (think 9am to 2am for at least 3-4 months of the year, settling down to 9am-10pm for the rest). You may be able to convince yourself otherwise, but personally I thought this made it very difficult to live a happy life that is healthy, contains strong relationships, allows for some pleasures and allows you to develop your thoughts and understanding of the world around you.

- I think the career and the legal / commercial mindset you develop whilst in the industry encourages aggressive individualism and a lack of trust. You are taught to see every person as a self-interested, rational profit maximising agent who cannot be relied upon. Whilst I think such a mindset may be appropriate for business, I found it increasingly difficult to differentiate my work and social mindset.

- The high wage at a young age has the potential to develop patterns of frivolous consumption – I have no real problem with this except (i) it is not necessary for the good life, it can only merely be a component of it and (ii) until we can say the industry is not regressive, such behaviour remains extremely perverse.

Conclusions

The piece above is very anecdotal and I'm sure some good arguments could be put forward as to how the various cogs involved in the savings-investment-return chain are merely participants in a competitive market place, and that the fees they earn are a simple function of supply and demand. I suspect, and part 3 will explore this further, that this sort of analysis is not quite right when you have a closed system (it is unlikely that one highly paid person will have a go at another highly paid person for fear of being labelled a hypocrite) and where the real monopoly power is with people (CEOs, city rainmakers, 'superstar' traders, city firm partners) rather than companies.

The other drawbacks: the city's brain drain, the (legal) predatory behaviour and the city life's conflict with the good life fit less squarely into a traditional economic framework. If we want to look to change these behaviours, a more creative approach will be required.

The piece above is very anecdotal and I'm sure some good arguments could be put forward as to how the various cogs involved in the savings-investment-return chain are merely participants in a competitive market place, and that the fees they earn are a simple function of supply and demand. I suspect, and part 3 will explore this further, that this sort of analysis is not quite right when you have a closed system (it is unlikely that one highly paid person will have a go at another highly paid person for fear of being labelled a hypocrite) and where the real monopoly power is with people (CEOs, city rainmakers, 'superstar' traders, city firm partners) rather than companies.

The other drawbacks: the city's brain drain, the (legal) predatory behaviour and the city life's conflict with the good life fit less squarely into a traditional economic framework. If we want to look to change these behaviours, a more creative approach will be required.

* All characters appearing in this work are fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental